Research Recruitment

How To Reduce Unconscious Recruitment Bias In User Research

Written by: Phil Hesketh

Published on:

We all have explicit and implicit biases that shape every aspect of our lives, and which affect the lives of other people we interact with — whether that’s our kids, our colleagues, or our research participants.

As a UX researcher, it’s critically important to be aware of the fact that you carry unconscious biases that can skew your participant recruitment pools and the outcomes of user interviews.

In this blog we’ll look at some of the biases in UX research that can come into play during the recruiting process, and when you’re running interviews—plus some steps you can take to reduce these and achieve more ethical, non-biased outcomes.

What is recruitment bias in research?

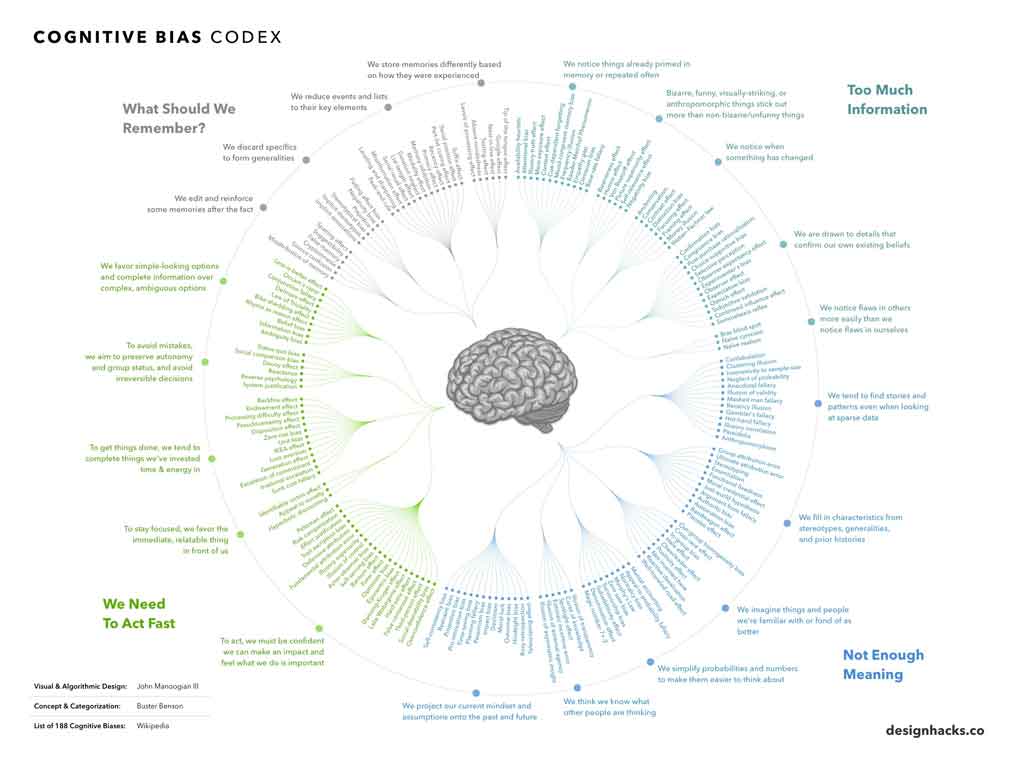

Scientists have identified over 150 types of explicit and implicit biases which, as the infographic below shows, is a lot to take into account when you’re working in the UX research field.

Infographic source: Visual Capitalist

When it comes to conducting ethical research, it’s most important to understand what you don’t understand — that you have a bunch of implicit biases tucked away in the deep recesses of your brain which can affect your approach to diversity, inclusion, and research strategies.

The Kirwan Institute at Ohio State University defines implicit bias as:

The attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. Activated involuntarily, without awareness or intentional control. Can be either positive or negative. Everyone is susceptible.

There’s no way to completely eliminate biases, especially the ones you don’t know you have, but you can take steps to reduce any known or potential biases when you’re running interviews and creating participant pools for your research sessions.

Recruitment bias

Recruitment bias can occur when your brain creates opinions about a user (or other potential participants) based on your initial impression of (or familiarity with) that person.

Whether you’re making a hiring decision or recruiting for interviews, recruitment bias is something you need to pay attention to.

This bias can stem from personal and cultural factors such as:

Where a person lives

Their name

Their age

A photo you saw of them

How much they earn

How they interacted with you on a phone call

Whether they made a bunch of typos in that last email they sent you

Whether you’ve just met them, versus knowing them for a long time

All of these tiny, seemingly insignificant impressions can form a bigger picture in your mind that can make you feel that one person is more suitable to be a research participant versus another person - and none of us are immune to this.

So while we think that we’re prioritizing diversity and inclusion in our research recruitment, that’s often not the case. Your biases are always at work in the background.

Even if you have a good understanding of how biases work, and what your own personal biases are or might be, it doesn’t always lead to better recruiting decisions. Plus, you might be faced with time or budget pressure, and trying to recruit quickly to make up the numbers you need for your study - all of which can lead to skewed participant pools.

Lesley Crane PhD, a Senior UX Researcher, shared some thoughts on how researchers can work towards reducing biases during the recruitment process:

Recruitment for user research projects is not a ‘standalone’ task but instead should be seen as an integral task of the research strategy.

Strategy starts with a research question (RQ) or hypothesis and this in turn is drawn from a consideration of the business aims, prevailing market conditions and known knowns of the users. The RQ frames around all three with the emphasis on known unknowns or even unknown unknowns.

The recruitment strategy is, then, driven by the question: who do we need to talk to in order to be able to confidently answer the RQ?

Common bias in recruitment results from bypassing those foundational steps and considerations. We often use the term ‘opportunity sample’ to describe the participants we seek to recruit. It’s tempting to recruit friends, family and colleagues to ‘fill in the numbers’ quickly and deliver results. That is a biased sample for all sorts of obvious reasons. Even viewed as an ‘indicative sample’, it is likely to deliver skewed results.

To avoid research and researcher bias, best practice is to build a participant profile, based on the research strategy and RQ, and recruit participants who complement this. The profile should describe basic demographic and skills features of users.

This, of course, all takes time - and recruitment is never easy. But the risk of ignoring these fundamental principles is misleading results with user research proceeding on little more than ‘hearsay’ and magical thinking.

Read more: How to write an effective recruitment email for a research study

What are the biases in user interviews?

Once you’ve recruited your participants (and hopefully reduced your biases during the process), there are a few common research bias types that can come into play when it’s time to run user interviews.

Interviewer bias

A researcher’s body language, word choices, line of questioning, and types of responses to feedback can all impact participants’ behaviours and answers during a user interview. And that’s before taking any cognitive biases into account.

How to reduce this

During interview sessions, it’s important that interviewers remain as neutral as possible with words and body language,, and avoid getting emotionally involved in any responses from participants. Research questions should be “open” and avoid leading questions that hint at the answers a participant thinks their researcher is looking for.

This requires a lot of practice and patience - but it allows participants to interpret questions and instructions, and give feedback in their own unique way without feeling any sort of pressure to conform to what they think the researcher is looking for.

Read more: The art of asking effective UX research questions

Confirmation bias

The Nielsen Norman Group defines confirmation bias as:

A cognitive error that occurs when people pursue or analyse information in a way that directly conforms with their existing beliefs or preconceptions. Confirmation bias will lead people to discard information that contradicts their existing beliefs, even if the information is factual.

In user interviews and usability tests, confirmation bias can show up when researchers favour participant responses that align with their own beliefs about the study at hand.

When a participant gives an answer that goes against a researcher’s assumptions, or the data they already have that supports these assumptions, this new user feedback can be skimmed over or ignored by a researcher based on the fact that it doesn’t line up with what they believe.

As a result, the whole research study, and even the UX design itself can be skewed by not taking this type of fresh participant feedback into account.

How to reduce this

Going into an interview with an awareness of confirmation bias is a great start to avoiding this common trap. Researchers need to look into their own existing assumptions about a study and how people are experiencing a product, and keep an open mind about anything they hear that contradicts these beliefs.

It’s important that researchers actively listen to all participants before drawing conclusions, and pay attention to any different information that comes up in their interview sessions.

False consensus bias

When a researcher projects their own behaviours and reactions onto a participant during a research study, assuming that a user would behave or think in the same way they do — this is known as a false-consensus bias.

How to reduce this

Researchers need to be aware that “you are not the user”, and that participants being interviewed will have answers, behaviours, choices, and judgments about a product that are very much their own.

It’s essential for researchers to remain as neutral as possible in their questions, responses, and body language so they don’t project their false consensus bias onto participants — and that they keep their mind wide open about how users are actually experiencing a product.

Anchoring bias

The anchoring bias (aka anchoring principle) describes a participant’s tendency to subconsciously rely on the first piece of information they’re given about a topic or product, and whether this information has a positive or negative skew.

In turn, this can make them feel more positive or negative about things like:

Product pricing

Customer service

Product usability

Anchoring is a technique used on a lot of software pricing pages to draw a user’s immediate attention to the most expensive pricing plan, making it look like the best value out of all the other options.

In user interviews, this bias can heavily influence participant responses about their behaviour using a product, and their satisfaction with a product or service,

How to reduce this

Participants can be affected by the sequence or wording of questions. It can be helpful to start your user interviews with a small number of participants so you can analyze and optimize your research questions before launching them to the rest of your participant pool.

Standardized, neutral questions should be used throughout the study, and it can be useful to mix up the order of any multi-choice questions (e.g. descending / ascending prices) to give a more balanced pool of responses.

Framing effect

The framing effect is a type of cognitive bias where humans make decisions based on the way information is presented or worded, irrespective of what the information is.

In user interviews this bias occurs when questions are worded to highlight positives or negatives, or when leading questions are presented that move a participant towards a certain type of response.

For example, humans are predisposed to avoiding pain over pursuing pleasure, and picking gains over losses, so any interview questions that subconsciously point them in one of these directions can affect the outcome of a study.

How to reduce this

Standardizing and testing interview questions is a good step towards reducing the framing effect. Researchers should also practice restating questions in different ways, and be able to rework a question from having a positive or negative skew to something neutral.

For example, researchers should avoid leading questions such as “How would you rate our amazing product on a scale of 1-10” and replace it with a neutral question like “How would you rate our product on a scale of 1-10” instead.

Affinity bias

This bias is also known as the “similarity bias”. It is an implicit bias that can occur when someone feels more comfortable around a person that is like them in some way - whether that’s through shared interests, cultures, or the small town they grew up in.

For example, a golf-loving UX researcher might favor the answers of a participant that they know also enjoys golf. Or a participant might feel more comfortable giving deep, meaningful interview responses to a researcher that they’ve previously met at a conference.

How to reduce this

It can be difficult to reduce unconscious bias in user interviews. Due to its innate nature in all of use, affinity bias can cause snap judgments to be made about a participant and their responses if a researcher feels they have nothing at all in common with the person they’re talking to.

Growing awareness and getting training around this bias can help researchers understand how this bias works, and how it can impact user interview sessions.

Sociability desirability bias

Everyone just wants to be liked, and it’s no different for user interview participants. During interview sessions, participants might take subtle cues from their interviewers, or from the questions themselves, and either skew their answers or exaggerate their responses in order to sound more likable and knowledgeable.

How to reduce this

To counter this bias, researchers need to examine methods of getting their participants to behave and respond as naturally and honestly in an interview environment as possible.

This can include taking steps like:

Guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality for participants

Collecting informed consent

Being transparent about your data management process

Asking questions in a neutral way

Wrapping up

So - how do you plan to reduce bias in your own UX research? Being aware that this is a problem all researchers face is a great start.

By learning about the different types of implicit biases that can affect your recruitment and user interview processes, you can begin to identify these in yourself and in other people on your team. This can enable you to develop strategies and protocols to ensure the effect of any potential biases are kept to a minimum during research studies.

If you’re looking to carry out UX research studies for your organization, Consent Kit can help you formalize your recruitment process, manage participant data with ease, and ensure your studies are accessible, compliant, and efficient. Try it free for 14 days.